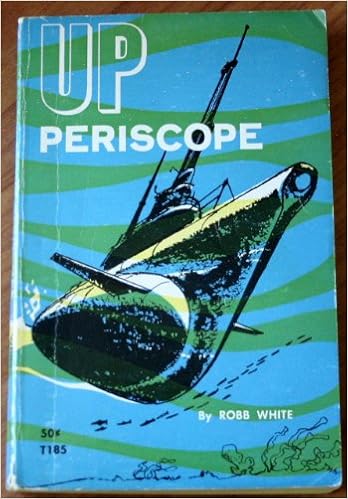

According to Jan Bloom’s Who Should We Then Read, Volume 2, author Robb White’s books are “high action, well-written adventure yarns peopled with realistically drawn, likable characters in plausible yet exciting situations.” This particular yarn is a World War II submarine adventure that takes place in the South Pacific. Kenneth Braden, lieutenant (junior grade), U.S. Naval Reserve, volunteers for an unnamed job while he’s in Underwater Demolition School, and he soon finds himself in Hawaii, Pearl Harbor, talking to an admiral about doing something “hard, lonely, and dangerous” somewhere in the Pacific. Ken can take the job or back out. Of course, he decides to go for it.

According to Jan Bloom’s Who Should We Then Read, Volume 2, author Robb White’s books are “high action, well-written adventure yarns peopled with realistically drawn, likable characters in plausible yet exciting situations.” This particular yarn is a World War II submarine adventure that takes place in the South Pacific. Kenneth Braden, lieutenant (junior grade), U.S. Naval Reserve, volunteers for an unnamed job while he’s in Underwater Demolition School, and he soon finds himself in Hawaii, Pearl Harbor, talking to an admiral about doing something “hard, lonely, and dangerous” somewhere in the Pacific. Ken can take the job or back out. Of course, he decides to go for it.

I won’t spoil the story by telling what Ken’s job entails, but it does involve a great deal of time on a submarine. Both Ken and the readers of the novel learn a lot about submarines by the time the story is over. I knew almost nothing about submarines and submarine warfare when I started reading, and now I know . . . a little, not because there’s only a little information in the book, but mostly because I could only take in and assimilate so much. Readers who are really interested in submarine warfare will find the story absorbing and informative, and I assume the details are accurate since Mr. White served in the U.S. Navy himself during World War II. Suffice it to say I enjoyed this action tale, and World War II buffs or submarine aficionados will enjoy it even more than I did.

Apparently, the book was popular in its time, or else Robb White had connections in Hollywood. The novel was published in 1956, and it was made into a movie, starring James Garner, in 1959. White’s memoir, Our Virgin Island, about the Pacific island he and his wife bought for $60.00 and lived on before the war, was filmed as Virgin Island in 1958. The movie starred John Cassavetes, Sidney Poitier, and Ruby Dee. (White did write for Hollywood, so I guess he had connections.)

The author is just about as fascinating as his novel. He was born in the Philippines, a missionary kid. He learned to sail at an early age, graduated from the Naval Academy, and loved the sea. But he also wanted to be a writer, and he wrote magazine articles, screenplays, three memoirs, and more than twenty novels. His novels were mostly marketed to what we would now call the young adult market, but Up Periscope at least is not about teens, but rather adult men, fighting in an adult war. The only reason it might be considered a “children’s” or “young adult” novel as far as I can see is that there is a distinct lack of bad language and sexual content, a welcome relief from modern young adult novels. I counted only one “damn”, and on the flip side, several instances in which the men pray in a very natural, fox-hole way for God to save them from impending death. There is some war nastiness and violence, but that’s to be expected in a war novel. I think anyone over the age of twelve or thirteen could appreciate this thrilling story of espionage and submarine derring-do.

Only a couple of Robb White’s books remain in print; the rest are available at wildly varying prices from Amazon or other used book sellers. On the basis of just having read this one (and Jan Bloom’s recommendation) I would recommend his novels for your World War II-obsessed readers, and I would be quite interested in reading Mr. White’s three memoirs: Privateer’s Bay, Our Virgin Island, and Two on the Isle.