1. 18 Washington Square South: A Comedy in One Act, 1944. Ms. L’Engle actually wrote several plays and was an actress herself before her marriage, but this is one of the few that appears in the bibliography at her website.

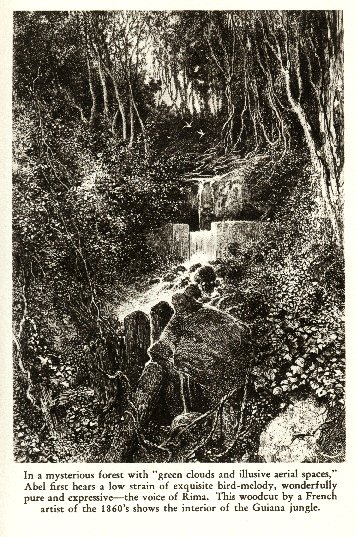

2. The Small Rain, 1945. Madeleine L’Engle’s first published novel tells the story of young Katherine Forrester, daughter of two famous musicians, who discovers in herself her own musical talent. This one is a beautifully realized coming-of-age novel set in Europe and New York City in the years before World War II. Semicolon review here.

3. Ilsa, 1946. Has anyone read this? Is it a novel or a play?

4. And Both Were Young, 1949, is another boarding school story starring artist Philippa Hunter who is miserable until she meets Paul and learns from him how to confront the past and overcome her self-doubt. I read this book a few months ago as a part of my Madeleine L’Engle project, but I never got around to writing about it here on the blog, maybe because I didn’t like it as much as I do her other books.

5. Camilla Dickinson, 1951. Republished in 1965 as simply Camilla, probably reworked to some extent. Semicolon review here.

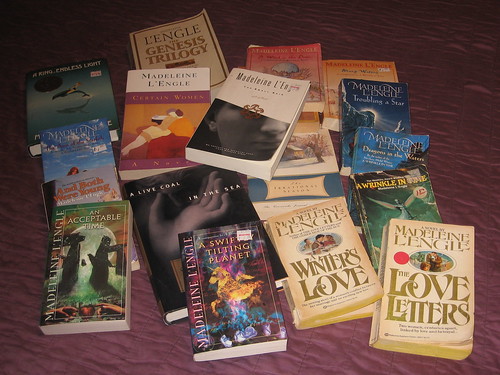

6. A Winter’s Love, 1957. Semicolon review here.

7. Meet the Austins, 1960. The first in the Austin family series of books.

8. A Wrinkle in Time, 1962. Madeleine L’Engle’s most famous book, winner of the Newbery Award in 1963, is deserving of the praise it gets. Meg Murry, her brother Charles Wallace the genius, and her friend Calvin “tesser” through space and time to rescue Meg’s father from IT.

9. The Moon By Night, 1963. The Austin family goes on a cross-country camping trip, and Vicky, age 15, meets some interesting characters, including Zachary, a poor little rich boy who is alternately fascinating and alarming. This one moves into Young Adult territory with romance, but nothing salacious.

10. The Twenty-Four Days Before Christmas, 1964. Christmas with the Austins.

11. The Arm of the Starfish, 1965. Polyhymnia (Polly) O’Keefe is the daughter of Meg (Murry) and Calvin O’Keefe from A Wrinkle in TIme. She becomes involved, along with a young student, Adam Eddington, in a complicated episode of scientific espionage.

12. Camilla, 1965. Semicolon review here.

13. The Love Letters, 1966. The story of a woman who is running away from a difficult marriage. She runs to Portugal, of all places, where she learns about love and responsibility and commitment from a 17th century Portuguese nun who broke her vows for the sake of a handsome French soldier. My favorite Madeleine L’Engle novel. (Adult) Semicolon review here.

14. A Journey With Jonah (a play), 1967.

15. The Young Unicorns, 1968. The Austin family is living in New York City; however, the story focuses on a couple of new friends of the Austins, pianist Emily Gregory and former gang member Dave Davidson. It’s a very sixties YA novel, featuring street gangs, lasers, and mad scientists.

16. Dance in the Desert, 1969.

17. Lines Scribbled on an Envelope and Other Poems, 1969

18. The Other Side of the Sun, 1971. The setting is early twentieth century South Carolina. English bride Stella Renier must come to live with her new husband’s famiy while he goes travelling on business. Sort of Gothic in good way with spiritual/Christian themes. (Young adult or adult)

19. A Circle of Quiet, 1972. Autobiography about Ms. L’Engle’s life in a village, her familly and her early writing life.

20. The Wind in the Door, 1973. The second of the Time Quartet books. Instead of travelling through time and space, Meg must travel inside Charles Wallace to diagnose and cure a problem with Charles Wallace’s mitochondria. Semicolon review here.

21. Everyday Prayers, 1974

22. Prayers for Sunday, 1974

23. The Risk of Birth, 1974

24. The Summer of the Great Grandmother, 1974. Nonfiction counterpart to the fictional A Ring of Endless Light, the two books deal with the task of dying with dignity and role of families in the process of death and dying.

25. Dragons in the Waters, 1976. Murder, smuggling, and blackmail in Venezuela. This YA novel features Polly O’Keefe.

26. The Irrational Season, 1977. A follow-up to Circle of Quiet and Summer of the Great-Grandmother.

27. A Swiftly Tilting Planet, 1978. The third book in the so-called TIme Quartet, this novel is one part science fiction, one part historical fiction, and another part just plain weird —in a wonderful sort of way.

28. The Weather of the Heart, 1978

29. Ladder of Angels, 1979

30. The Anti-Muffins, 1980. A short book about the Austins and nonconformism.

31. A Ring of Endless Light, 1980. Vicky Austin and her family must come to terms with the impending death of Vicky’s garndfather, and Vicky must decide who she is and whom she can trust.

32. Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art, 1980. These essays on the intersection of faith and art are quite helpful and thought-provoking for Christian artists in particular. JR at brokenstainedglass has been blogging about the insights he has gleaned from this book for last couple of months (August-September, 2007).

33. A Severed Wasp, 1982. Katherine Forrester from A Small Rain returns as an elderly retired concert pianist who becomes entangled in the life of the characters who ive in and around the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City.

34. And It Was Good: Reflections on Beginnings, 1983.

35. A House Like a Lotus, 1984. Polly O’Keefe, nearly seventeen years old in this novel, travels to Cyprus and learns both discernment and acceptance in her relationships.

36. Trailing Clouds of Glory: Spiritual Values in Children’s Literature, 1985 (with Avery Brooke). Another excellent book about the art of writing particularly for Christian writers.

37. Many Waters, 1986. A fictionalization of the Biblical story of Noah and the ark, with time travel, unicorns, and nephilim thrown in. The main characters are Meg Murry’s twin brothers, Sandy and Dennys.

38. A Stone for a Pillow: Journeys with Jacob, 1986

39. A Cry Like a Bell, 1987

40. Two-Part Invention, 1988. The story of Madeleine’s marriage to actor Hugh Franklin.

41. An Acceptable Time, 1989. Polly O’Keefe returns in her fourth story, and the plot and themes hark back to those of Time Quartet: time travel, peoples and cultures of the past, healing, the power of love.

42. Sold Into Egypt: Joseph’s Journey into Human Being, 1989.

43. The Glorious Impossible, 1990.

44. Certain Women, 1992 is an adult novel about the Biblical King David and about a modern-day David, an actor who engages in serial polygamy in about the same way that David of the Bible loved many women and had many wives. Semicolon review here.

45. The Rock That is Higher, 1993

46. Anytime Prayers, 1994

47. Troubling a Star, 1994. Vicky Austin and Adam Eddington are in Antarctica where they resist those who are trying to exploit the continent’s natural resources. YA.

48. Glimpses of Grace, 1996 (with Carole Chase)

49. A Live Coal in the Sea, 1996. This adult novel returns to the character Camilla from the book of the same name and tells the story of her famiy, especially her son Taxi and granddaughter Raffi.

50. Penguins and Golden Calves: Icons and Idols, 1996

51. Wintersong, 1996 (with Luci Shaw). Poetry.

52. Bright Evening Star, 1997

53. Friends for the Journey, 1997 (with Luci Shaw). Reviewed here by Carol of Magistramater.

54. Mothers and Daughters, 1997 (with Maria Rooney). Maria Rooney is Madeleine L’Engle’s daughter.

55. Miracle on 10th Street, 1998

56. A Full House, 1999. A Christmas story about the Austin family and an unexpected Christmas baby.

57. Mothers and Sons, 1999 (with Maria Rooney)

58. Prayerbook for Spiritual Friends, 1999 (with Luci Shaw)

59. The Other Dog, 2001

60. Madeleine L’Engle Herself: Reflections on a Writing Life, 2001 (with Carole Chase)

61. The Ordering of Love: The New and Collected Poems of Madeleine L’Engle, 2005.