1242: The Inquisitor’s Tale: Or, The Three Magical Children and Their Holy Dog by Adam Gidwitz. travelers from across France cross paths at an inn and begin to tell stories of three children: Jeanne, a peasant girl who has visions, William, an oblate who is half-Saracen and half French, and Jacob, a Jewish boy with a gift for healing. These children may be saints, or they may be using evil magic to do wonders that will deceive the faithful. And the dog, Gwenforte, who once saved a child from a deadly serpent, may be resurrected, but can a dog really be a saint?

1242: The Inquisitor’s Tale: Or, The Three Magical Children and Their Holy Dog by Adam Gidwitz. travelers from across France cross paths at an inn and begin to tell stories of three children: Jeanne, a peasant girl who has visions, William, an oblate who is half-Saracen and half French, and Jacob, a Jewish boy with a gift for healing. These children may be saints, or they may be using evil magic to do wonders that will deceive the faithful. And the dog, Gwenforte, who once saved a child from a deadly serpent, may be resurrected, but can a dog really be a saint?

1606: Caravaggio: Signed in Blood by Mark Smith. For fifteen-year-old Beppo Ghirlandi, an indentured servant accused of murder, there is no one to turn to. The only person who will help him is the painter from across the piazza, the madman genius known as Caravaggio—-who, unfortunately, has serious troubles of his own.

1781: Ashes by Laurie Halse Anderson. The third book in the Seeds of America Trilogy chronicles the adventures of Isabel and Curzon after the winter at Valley Forge.

*1812: The Left-Handed Fate by Kate Milford. Lucy Bluecrowne and Maxwell Ault must find the three pieces of a strange and arcane engine they believe can stop the endless war raging between their home country of England and Napoleon Bonaparte’s France. But they are in America, where the Americans have just declared war on the British, and the engine is a prize that all three countries will fight to own.

1816: Secrets of the Dragon Tomb by Patrick Samphire. In this steampunk alternate history sci-fi novel, the evil Sir Titus takes Edward’s parents hostage to help him find a lost dragon tomb—on Mars. The political situation in the background of the story involves the British Empire on Earth as they fight the Napoleonic Wars.

1825: A Buss From Lafayette by Dorothea Jensen. Clara’s town is excited because the famous Revolutionary War hero, General Lafayette, is about to visit their state during his farewell tour of America.

1840-1877: In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse by Joseph Marshall. Jimmy McClean learns about his Lakota heritage from his grandfather and from stories about the hero Tasunke Witko, better known as Crazy Horse.

*1847: The Nine Lives of Jacob Tibbs by Cylin Busby. Jacob Tibbs, ship’s cat, chronicles the sometimes sad, sometimes exciting, adventures of the sailors aboard the Melissa Rae.

1866: Makoons by Louise Erdrich. Makoons, an Ojibwe boy, and his twin, Chickadee, travel with their family to the Great Plains of Dakota Territory. There they must learn to become buffalo hunters and once again help their people make a home in a new land.

c.1870: The Lie Tree by Frances Hardinge. . Faith Sunderly is a proper Victorian young lady who has always been told, and who believes, that she is inferior in every way to men. Her father, the Reverend Sunderly is not only a cleric but also a world famous paleontologist. Faith, too is interested in science and in anything that will impress her father and get him to pay attention to her, but when she begins to learn more about her father’s research, she also finds herself enmeshed in a web of lies and deceit that won’t let go.

c.1870: The Lie Tree by Frances Hardinge. . Faith Sunderly is a proper Victorian young lady who has always been told, and who believes, that she is inferior in every way to men. Her father, the Reverend Sunderly is not only a cleric but also a world famous paleontologist. Faith, too is interested in science and in anything that will impress her father and get him to pay attention to her, but when she begins to learn more about her father’s research, she also finds herself enmeshed in a web of lies and deceit that won’t let go.

1871: Cinnamon Moon by Tess Hilmo. Three children displaced by fires (The Great Chicago Fire and another in Wisconsin on the same day) must find a way to survive and thrive.

*1887: A Bandit’s Tale: The Muddled Misadventures of a Pickpocket by Deborah Hopkinson. Eleven year old Rocco must survive on the streets of New York City after his Italian parents sell him to a padrone who uses him to make money as a street musician.

1892: The Crimson Skew by S.E. Grove. Third book in the Mapmakers trilogy. Sophia Tims is coming home from a foreign Age, having risked her life in search of her missing parents. Now she is aboard ship, with a hard-earned, cryptic map that may help her find them at long last.

*1909: The Mystery of the Clockwork Sparrow and The Mystery of the Jewelled Moth by Katharine Woodfine. Mysteries abound in an early twentieth century London department store.

1910: Race to the South Pole by Kate Messner. Ranger of Time series. A time-traveling dog, Ranger, helps out during Captain Scott’s Terra Nova Expedition to Antarctica.

1920’s: Isabel Feeney, Star Reporter by Beth Fantaskey. 10 year old Isabel is obsessed with becoming a news reporter in 1920’s Chicago, where gangsters rule and the Tribune is the paper of record.

1929: The Eye of Midnight by Andrew Brumbach. On a stormy May day William and Maxine, cousins who hardly know each other, meet at the home of their mutual grandfather, Colonel Battersea. Soon after their arrival, Grandpa receives a secret telegram which takes the three of them to New York City. From there, the story rapidly becomes more and more frenzied, dangerous, and desperate as the children try to rescue Grandpa, find a lost package, decide whether or not to trust the courier, a girl named Nura, and work out their own new-found friendship.

1929: The Gallery by Laura Marx Fitzgerald. Twelve-year-old Martha works as a maid in the New York City mansion of the wealthy Sewell family. The other servants say Rose Sewell is crazy, but Martha believes that the paintings in the Sewell’s gallery contain a hidden message about Rose and about the other secrets in the Sewell mansion.

1934: Sweet Home Alaska by Carole Estby Dagg. Terpsichore’s father signs up for President Roosevelt’s Palmer Colony project, uprooting the family from Wisconsin to become pioneers in Alaska.

1934: Sweet Home Alaska by Carole Estby Dagg. Terpsichore’s father signs up for President Roosevelt’s Palmer Colony project, uprooting the family from Wisconsin to become pioneers in Alaska.

1939: You Can Fly: The Tuskegee Airmen by Carol Boston Weatherford. Verse novel about the struggles and achievements of the Tuskegee Airmen, an all-black air training program during World War II.

1940: Once Was a Time by Leila Sales. Time travel isn’t possible, is it? Or can time travel be the secret weapon that will allow the Allies to win World War II? And can friendship last over time when one friend gets displaced and can’t return to her own time?

1940’s: Projekt 1065: A Novel of World War II by Alan Gratz. 13-year-old Irish boy, Michael O’Shaunessey, becomes a spy in Nazi Germany.

1940’s: The Secret Horses of Briar Hill by Megan Shepard. Winged horses live in the mirrors of Briar Hill hospital. But only Emmaline can see them.

1940’s: The Charmed Children of Rookskill Castle by Janet Fox. During the Blitz, Katherine, Robbie and Amelie Bateson are sent north to a private school in Rookskill Castle in Scotland, a brooding place, haunted by dark magic from the past. But when some of their classmates disappear, Katherine has to find out what has happened to them.

1941: Bjorn’s Gift by Sandy Brehl. Sequel to Odin’s Promise by the same author. Mari, a young Norwegian girl, faces growing hardships and dangers in her small village in a western fjord during World War II.

1941: Aim by Joyce Moyer Hostetter. Fourteen-year-old Junior Bledsoe struggles with school and with anger—-at his father, his insufferable granddaddy, his neighbors, and himself—-as he desperately tries to understand himself and find his own aim in life.

*1942: Skating With the Statue of Liberty by Susan Lynn Meyer. Gustave, a twelve-year-old French Jewish boy, has made it to America at last. After escaping with his family from Nazi-occupied France, he no longer has to worry about being captured by the Germans. But life is not easy in America, either.

1942: Wolf Hollow by Lauren Wolk. Annabelle has lived a mostly quiet, steady life in her small Pennsylvania town. Then, new student Betty Glengarry walks into her class. Betty quickly reveals herself to be cruel and manipulative, and while her bullying seems isolated at first, things quickly escalate, and reclusive World War I veteran Toby becomes a target of her attacks.

1942: Paper Wishes by Lois Sepahban. Ten year old Manami, a Japanese American girl sent to an internment camp with her family, clings to the hope that somehow grandfather’s dog, Yujiin, will find his way to the camp and make her family whole again.

1942: The Bicycle Spy by Yona Zeldis McDonough. Marcel, a French boy, dreams of someday competing in the Tour de France, the greatest bicycle race. But ever since Germany’s occupation of France began the race has been canceled. Now there are soldiers everywhere, and Marcel bicycle may be useful for more important things than winning a race.

1942: Brave Like My Brother by Marc Nobleman. An American soldier in WWII England shares his war experiences with his 10-year-old brother via letters.

1952: Making Friends With Billy Wong by Augusta Scattergood. Azalea Ann Morgan leaves her home in Tyler Texas to stay with her injured Grandma and help out for the summer. Although Azalea has difficulty making new friends, she and Billy Wong have adventures together in the small town in Arkansas where Azalea’s grandma lives.

1952: Making Friends With Billy Wong by Augusta Scattergood. Azalea Ann Morgan leaves her home in Tyler Texas to stay with her injured Grandma and help out for the summer. Although Azalea has difficulty making new friends, she and Billy Wong have adventures together in the small town in Arkansas where Azalea’s grandma lives.

1969: Ruby Lee and Me by Shannon Hitchcock. A North Carolina town hires its first African-American teacher in 1969, and two girls–one black, one white–confront the prejudice that challenges their friendship.

1973: Waiting for Augusta by Jessica Lawson. Ben Hogan Putter just lost his dad to cancer. Now Ben has a permanent lump in his throat that he believes is an actual golf ball, and his barbecue-loving, golf-loving daddy is speaking to him from beyond the grave, asking Ben to take his ashes to Augusta, Georgia, home of the most famous golf course in the world.

1975: Raymie Nightingale by Kate DiCamillo. If Raymie Clarke can just win the Little Miss Central Florida Tire competition, then her father, who left town two days ago with a dental hygienist, will see Raymie’s picture in the paper and (maybe) come home.

*1978: It Ain’t So Awful, Falafel by Firoozeh Dumas. Zomorod Yusefzadeh is living in California with her Iranian family during the Iran hostage crisis. No wonder she wants to change her name to Cindy!

*1984: Time Traveling with a Hamster by Ross Welford. On his twelfth birthday, Al receives two gifts: a hamster and a letter from his deceased dad. The letter informs Al that it might be possible for him to use his dad’s time machine to go back in time and prevent his father’s death. Unfortunately, it’s not easy for Al to even get to the place where his dad’s time machine is waiting, not to mention the difficulty of manipulating past events to change the future.

1989: Cloud and Wallfish by Anne Nesbet. Noah Keller has a pretty normal life, until one wild afternoon when his parents pick him up from school and head straight for the airport, telling him on the ride that his name isn’t really Noah and he didn’t really just turn eleven in March. Now, the family is headed for East Berlin, and Noah/Jonah mustn’t ask any questions.

2001: Nine, Ten: A September 11 Story by Nora Raleigh Baskin. Four children living in different parts of the country are affected by the events of September 11, 2001.

2001: Towers Falling by Jewell Parker Rhodes. Actually set in 2016, this story is about three schoolchildren who are studying the events of 9/11 and who come to see its impact on their own lives.

2011: The Turn of the Tide by Roseanne Parry. Two cousins on opposite sides of the Pacific experience the 2011 tsunami.

A few notes about this list:

Some of the blurbs are taken from Amazon or from Goodreads and edited to fit my list.

My favorites of the ones I’ve read are *starred. No, I haven’t read all of these. Links are to Semicolon reviews of the books that I have read and reviewed.

Some of these are straight historical fiction, and others are time travel or other fantasy books set mostly in the time period indicated.

Finally, we need more (excellent!) books for middle grade readers set in ancient times and in the middle ages or at least before 1800. I know of lots of older books set in these time periods, but not many are being published now. Too much research required? Or just a lack of interest?

This third and final book in Ms. Anderson’s Seeds of America trilogy wraps up the story of Curzon and Isabel, the black teens who have weathered the vicissitudes of the American revolution and of slavery, freedom, and re-capture and are now near their goal: the liberation of Isabel’s younger sister, Ruth, and her restoration to freedom and the only family she has, Isabel.

This third and final book in Ms. Anderson’s Seeds of America trilogy wraps up the story of Curzon and Isabel, the black teens who have weathered the vicissitudes of the American revolution and of slavery, freedom, and re-capture and are now near their goal: the liberation of Isabel’s younger sister, Ruth, and her restoration to freedom and the only family she has, Isabel.

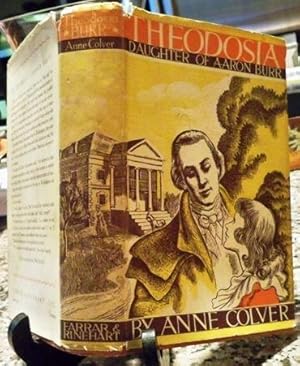

My daughters have become engrossed in listening to the soundtrack from the Broadway musical, Hamilton, and therefore I have listened to bits and pieces of it quite a few times over the past couple of weeks. (Warning: there’s some fairly foul language in the lyrics to the musical, as well as some lurid gossip about the main characters. On the other hand, some of the lyrics are quite funny and witty.) As one thing leads to another, I noticed this book on the shelves of my library and decided to read it. Theodosia Burr Alston was the only (legitimate)* daughter of Aaron Burr, who figures prominently in the life and, of course, death of Alexander Hamilton.

My daughters have become engrossed in listening to the soundtrack from the Broadway musical, Hamilton, and therefore I have listened to bits and pieces of it quite a few times over the past couple of weeks. (Warning: there’s some fairly foul language in the lyrics to the musical, as well as some lurid gossip about the main characters. On the other hand, some of the lyrics are quite funny and witty.) As one thing leads to another, I noticed this book on the shelves of my library and decided to read it. Theodosia Burr Alston was the only (legitimate)* daughter of Aaron Burr, who figures prominently in the life and, of course, death of Alexander Hamilton.