I read over 200 books in 2014. Of those, if I counted right, only twenty-two were nonfiction. So, when I say the “11 best” or 11 favorite”, I’m including half of the nonfiction books I read this past year. The first two on the list were my favorites; the rest are in no particular order.

I read over 200 books in 2014. Of those, if I counted right, only twenty-two were nonfiction. So, when I say the “11 best” or 11 favorite”, I’m including half of the nonfiction books I read this past year. The first two on the list were my favorites; the rest are in no particular order.

The Last Lion 2: Winston Spencer Churchill Alone, 1932-40 by William Manchester. I love Winston Churchill. I would have been afraid or at least disinclined to work for him or to eat at his dinner table; he did not suffer fools gladly and did not treat even his employees and friends with great consideration for their comfort. But reading about him is a delight.

Seeking Allah, Finding Jesus: A Devout Muslim Encounters Christianity by Nabeel Qureshi. Good Christian apologetics, good story.

Agent Zigzag: A True Story of Nazi Espionage, Love, and Betrayal by Ben MacIntyre.

The Book Whisperer: Awakening the Inner Reader in Every Child by Donalyn Miller.

Blue Marble: How a Photograph Revealed Earth’s Fragile Beauty by Don Nardo. The story of the iconic picture of earth from space taken by the astronauts of Apollo 17.

The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History by Robert M. Edsel. Skip or skim the boring parts, but most of this one is a fascinating look at the rescue of art treasures from Nazi theft and from Allied ignorance.

Rich in Love: When God Rescues Messy People by Irene Garcia. People and relationships are messy, and Ms. Garcia doesn’t pretend that all of the stories of her many foster children and adopted children turn out well. Some are still struggling with bad choices and bad beginnings. But this was ultimately a hope-filled book about the way God uses imperfect, messed-up people to sow His grace into the world.

The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America by Erik Larson. Kind of grisly, but fascinating in its detail about a vision of progress and light alongside a serial killer’s vision of deceit and murder.

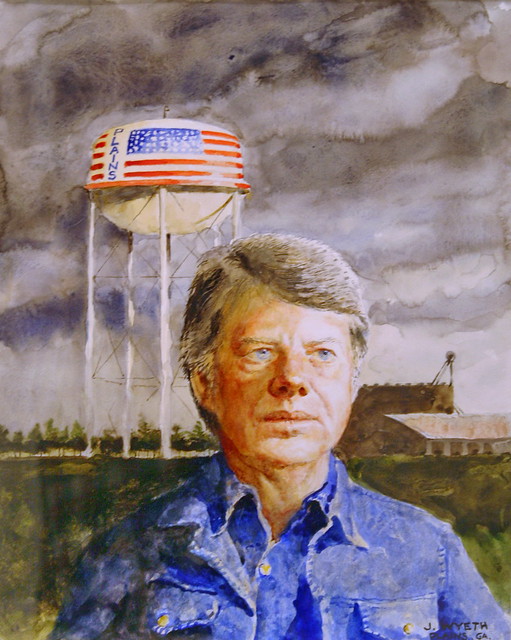

Everybody Paints! The Lives and Art of the Wyeth Family by Susan Goldman Rubin. Interesting family, interesting book, written for children but it tells as much as I wanted to know.

One Summer: America, 1927 by Bill Bryson. I just finished this one a few days before Christmas. I laughed, I gasped, I read passages out loud to my unappreciative family. In short, I was captivated by reliving the summer of 1927.