I’m participating in only a couple of reading challenges this year, and the one I’m most enjoying so far is the U.S. Presidents Reading Project. I have a goal of reading one biography of a president per month, and I’m on target, having finished a biography of Washington and having read about halfway through John Adams by David McCullough. Here’s a list of some of the biographies I plan to read for this project. If you have any suggestions for the presidents whose names have no biography listed, or if you think I should choose another book other than the one I have listed, please leave any and all suggestions in the comments.

1. George Washington, 1789-97 Washington: The Indispensable Man by James Thomas Flexner. Semicolon review here.

2. John Adams, 1797-1801 (Federalist) John Adams by David McCullough. I also plan to watch the mini-series based on this book.

3. Thomas Jefferson, 1801-9 (Democratic-Republican) I’ve taken a dislike to Jefferson after the Washington biography (not too much Jefferson in the John Adams book yet, but Jefferson probably won’t be a hero in that one either). So I’m not sure which Jefferson bio to choose, one that’s flattering to restore my faith in this rather contradictory and enigmatic president, or one that’s iconoclastic to reinforce my antipathy.

Beth Fish reviews Twilight at Monticello by Alan Pell Crawford.

4. James Madison, 1809-17 (Democratic-Republican) The Great Little Madison by Jean Fritz. Yes, this one is a children’s book. I plan to read children’s books for some of these presidents because sometimes they’re better than the adult tomes. And I may use the children’s biographies in future school years. And reading a children’s biography may tell me whether or not I want to read more about a particular president.

5. James Monroe, 1817-25 (Democratic-Republican) James Monroe: The Quest for National Identity by Harry Ammon.

6. John Quincy Adams, 1825-29 (Democratic-Republican) The Life and Times of Congressman John Quincy Adams by Leonard L. Richards.

7. Andrew Jackson, 1829-37 (Democrat) American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House by Jon Meacham. This one is displayed prominently in the bookstores, and it looks interesting.

Also, there’s Old Hickory: Andrew Jackson and the American People by Albert Marrin.

8. Martin Van Buren, 1837-41 (Democrat)

9. William Henry Harrison, 1841 (Whig) Mr. Jefferson’s Hammer: William Henry Harrison and the Origins of American Indian Policy by Robert M. Owens

10. John Tyler, 1841-45 (Whig) John Tyler, the Accidental President by Edward P. Crapol

11. James Knox Polk, 1845-49 (Democrat) Polk: The Man Who Transformed the Presidency and America by Walter R. Borneman.

12. Zachary Taylor, 1849-50 (Whig)

13. Millard Fillmore, 1850-53 (Whig)

14. Franklin Pierce, 1853-57 (Democrat)

15. James Buchanan, 1857-61 (Democrat)

16. Abraham Lincoln, 1861-65 (Republican) Whereas with several of preceding presidents there is a dearth of good biographies to choose from, for Abraham Lincoln, it’s more like an embarrassment of riches. Which biography of LIncoln should I read? Maybe, Commander and Chief: Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War by Albert Marrin. I like Mr. Marrin’s books.

17. Andrew Johnson, 1865-69 (Democrat/National Union) The Avenger Takes His Place: Andrew Johnson and the 45 Days That Changed the Nation by Howard Means.

18. Ulysses Simpson Grant, 1869-77 (Republican) Grant: A Biography by William McFeely.

Or, Unconditional Surrender: U. S. Grant and the Civil War by Albert Marrin.

19. Rutherford Birchard Hayes, 1877-81 (Republican) Fraud of the Century: Rutherford B. Hayes, Samuel Tilden, and the Stolen Election of 1876 by Roy Morris Jr. Read, 2014.

20. James Abram Garfield, 1881 (Republican) Dark Horse : The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield by Kenneth D. Ackerman

21. Chester Alan Arthur, 1881-85 (Republican) Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester Alan Arthur by Thomas C. Reeves.

22. Grover Cleveland, 1885-89 (Democrat) To the Loss of the Presidency (Grover Cleveland a Study in Courage, Vol. 1) by Allan Nevins.

23. Benjamin Harrison, 1889-93 (Republican)

24. Grover Cleveland, 1893-97 (Democrat) Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage by Allan Nevin. (2 volumes)

25. William McKinley, 1897-1901 (Republican) In the Days of McKinley by Margaret Leech.

26. Theodore Roosevelt, 1901-9 (Republican) Mornings on Horseback: The Story of an Extraordinary Family, a Vanished Way of Life and the Unique Child Who Became Theodore Roosevelt by David McCullough

Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of Modern America by Albert Marrin.

27. William Howard Taft, 1909-13 (Republican)

28. Woodrow Wilson, 1913-21 (Democrat) Woodrow Wilson: Princeton to the Presidency by W. Barksdale Maynard.

29. Warren Gamaliel Harding, 1921-23 (Republican) Florence Harding: The First Lady, The Jazz Age, And The Death Of America’s Most Scandalous President by Carl Sferrazza Anthony (Read, January, 2105). Wow, Harding was a cad and a person of low character. I didn’t finish or review this bio because it was so depressing.

The Strange Death of President Harding by Gaston B. Means and May Dixon Thacker.

30. Calvin Coolidge, 1923-29 (Republican) A Puritan in Babylon: The Story of Calvin Coolidge by William Allen White OR The Autobiography Of Calvin Coolidge by Calvin Coolidge.

31. Herbert Clark Hoover, 1929-33 (Republican)

32. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1933-45 (Democrat) Franklin and Winston: An Intimate Portrait of an Epic Friendship by Jon Meacham. I rather like Churchill, FDR not so much, so this one sounds like something I could enjoy and learn from. *I actually read and enjoyed FDR and the American Crisis by Albert Marrin in October, 2015.

33. Harry S. Truman, 1945-53 (Democrat) Truman by David McCullough. 1993 Pulitzer Prize winner.

34. Dwight David Eisenhower, 1953-61 (Republican) Ike: An American Hero by Michael Korda.

My Three Years with Eisenhower by Captain Harry Butcher.

Crusade in Europe by Dwight Eisenhower.

35. John Fitzgerald Kennedy, 1961-63 (Democrat) I might just re-read Profiles in Courage in lieu of a biography of this overrated (IMHO) president.

36. Lyndon Baines Johnson, 1963-69 (Democrat) The Years of Lyndon Johnson: Master of the Senate, Volume 3 (2003 Pulitzer Prize for biography) by Robert Caro.

37. Richard Milhous Nixon, 1969-74 (Republican)

38. Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr , 1974-77 (Republican)

39. James Earl Carter, 1977-81 (Democrat) An Hour Before Daylight: Memories of a Rural Boyhood by Jimmy Carter

40. Ronald Wilson Reagan, 1981-89 (Republican) Ronald Reagan: How an Ordinary Man Became an Extraordinary Leader by Dinesh D’Souza

41. George Herbert Walker Bush, 1989-1993 (Republican)

42. William Jefferson Clinton, 1993-2001 (Democrat)

43. George W. Bush, 2001-2009 (Republican)

44. Barack Hussein Obama, 2009- (Democrat)

I guess for most of the presidents I haven’t decided on a biography or related book. I’m taking suggestions, folks.

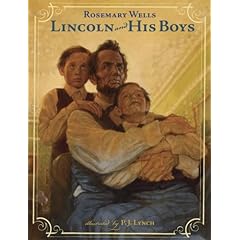

Rosemary Wells’ fictionalized memoir of Abraham Lincoln and his sons, Willie and Tad, was nominated for a Cybil Award. So I read it. Of course, it reminded me of F.N. Monjo’s (out of print) classic in the same genre and with the same subject, Me and Willie and Pa, published in 1973. So I got that one down and re-read it.

Rosemary Wells’ fictionalized memoir of Abraham Lincoln and his sons, Willie and Tad, was nominated for a Cybil Award. So I read it. Of course, it reminded me of F.N. Monjo’s (out of print) classic in the same genre and with the same subject, Me and Willie and Pa, published in 1973. So I got that one down and re-read it.  Both books present the same picture of Lincoln as a father, indulgent to a fault. He allowed his boys to invade cabinet meetings, play soldier by ordering guards around, and accompany him on visits to the troops. When either the politicians or Mary Lincoln complained that Mr. Lincoln was spoiling the boys, both books agree that Lincoln paid them no mind and continued to allow his sons the freedom to be rowdy, noisy, and spirited. We’ll never know if Lincoln’s indulgent child-rearing practices would have made Tad and Willie into strong, independent men or spoiled rotten brats. Willie died uirng Lincoln’s first term in office, and Tad died in Chicago three months after his eighteenth birthday. Maybe in light of their early deaths, it’s good to know that they had a very happy childhood and a loving father.

Both books present the same picture of Lincoln as a father, indulgent to a fault. He allowed his boys to invade cabinet meetings, play soldier by ordering guards around, and accompany him on visits to the troops. When either the politicians or Mary Lincoln complained that Mr. Lincoln was spoiling the boys, both books agree that Lincoln paid them no mind and continued to allow his sons the freedom to be rowdy, noisy, and spirited. We’ll never know if Lincoln’s indulgent child-rearing practices would have made Tad and Willie into strong, independent men or spoiled rotten brats. Willie died uirng Lincoln’s first term in office, and Tad died in Chicago three months after his eighteenth birthday. Maybe in light of their early deaths, it’s good to know that they had a very happy childhood and a loving father.