Hitchhiking Vietnam: A Woman’s Solo Journey in an Elusive Land by Karin Muller. Globe Pequot Press, 1998.

Hitchhiking Vietnam: A Woman’s Solo Journey in an Elusive Land by Karin Muller. Globe Pequot Press, 1998.

I enjoyed reading this memoir/travelogue of an American woman who spent seven months in post-war Vietnam, traveling by bus, motorcycle, bicycle and on foot from the Mekong Delta to the northern border with China and along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. She endured hardships and discomforts that would have sent me scuttling back to Texas within the first few pages, but I never was sure why. Ms. Muller tries to explain in the book. She writes about her mother’s stories of growing up in Africa and about the sense of adventure she inherited from her somewhat peripatetic parents. However, and maybe it was just my underdeveloped sense of adventure, the Vietnam Karin Muller describes is not inviting; it’s full of greed, bribery, poverty, alcoholism, and political corruption. And that’s just among the tourist population. The Vietnamese themselves, with a few exceptions, are out to get as many American dollars as possible or in the case of the government bureaucrats and the police, determined to make travel as difficult as possible for anyone with fair skin and a camera. Muller keeps lookng for a “village” where she can live for awhile and enjoy her Rousseau-inspired vision of happy natives living simple, uncluttered lives. She does find such villages a couple of times during her odyssey, but the visit usually comes to an abrupt end when government officials or basic materialism intervene.

The book, while fascinating in its descriptions of modern Vietnam from a foreigner’s perspective, didn’t stir my sense of adventure, nor did it make me want to hop on a plane for Vietnam. But don’t go by me. Eldest Daughter told me today that I was a stick in the mud, and my idea of a wonderful trip involves London, Oxford, Cambridge, and Stratford-on-the-Avon. I think I’ll stick with the armchair travel route to Asia since I’m spoiled by basic conveniences such as flush toilets and clean drinking water and food that doesn’t contain parasites.

One thing I found interesting, and sad, is that Vietnam seems to be going the way of China with its one-child policy as exemplified in this account of a conversation that the author had with a group of Vietnamese soldiers:

“To my surprise, not one of them had more than two children in a land that valued family above all else, the larger the better. My driver reminded me of the billboards I had seen in almost every town, proclaiming the new government in favor of small families, with captions reading, ‘Have one or two children!’ Army doctrine apparently took a more active role, and soldiers were demoted one star for every child more than two.”

There were other stories that shed light on the current state of the people of Vietnam: Ms. Muller’s friend and erstwhile guide Tam tells her about his struggles to survive in post-war Vietnam as a former interpreter for the U.S. Marines during the war.

One chapter focuses on the Zao village in northern Vietnam where Ms. Muller spends a week living with a family of rice-growers. It’s somewhat idyllic, with a patriarchal extended family working together to build the family’s fortunes and find marriages for its young men and women. However, the chapter also includes a badly burned baby with no medical care other than a tube of athlete’s foot medication salvaged from the Red Cross at some time in the history of the village. Not so idyllic after all.

In the final analysis, I just couldn’t figure out why Karin Muller wanted to travel through Vietnam. She seemed to have some compassion for the people whose lives were so poverty-stricken. But harking back to a bad experience in the Peace Corps in the Philippines, Ms. Muller doesn’t think she can make a difference in the people’s lives nor that she has any right to try. She does try to rescue some endangered animals (a gibbon, baby leopards, and an eagle) destined for the medicinal markets of China, but the results of that attempt at good works are mixed. She says at the beginning of the book that she wants to understand the Vietnamese people and their ability to forgive their former enemies, the Americans. Maybe cultural understanding was enough of a goal to get her through sleepless nights in squalid surroundings, dysentery and scurvy, and countless bureaucratic tangles and arguments.

It wouldn’t be enough for me. I’m not only a stick in the mud; I’m also a wimp.

Other Vietnam books I have read or want to read:

I’ve heard that The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien is a good read about the Vietnam War and the American soldiers who fought and died in it. I have the book on my shelf, but I haven’t read it yet. I did read Phillip Caputo’s classic memoir A Rumor of War (a long time ago), and I remember it as fascinating, disturbing, but sometimes simplistic. Either of these books would probably teach the reader a lot about Americans in Vietnam, but not too much about Vietnam or the Vietnamese themselves.

For children or yong adults the following books might be helpful in understanding Vietnamese culture and interactions:

Goodbye, Vietnam by Gloria Whelan.

Cracker: The Best Dog in Vietnam by Cynthia Kadohata. Semicolon review here.

When Heaven Fell by Carolyn Marsden. Semicolon review here.

Fallen Angels by Walter Dean Myers. Perry, a teenager from Harlem, experiences the horrors of the Vietnam War.

Paradise of the Blind by Thu Huong Duong and Nina McPherson. This book is a YA coming of age novel of post-war Vietnam, originally written in Vietnamese, banned in Vietnam, and later translated into English and published in the U.S. It sounds like a wonderful window into Vietnam written by a Vietnamese author.

For today’s round-up of reviews of titles set in Southeast Asia or written by Southeast Asian authors, check out the One Shot World Tour at Chasing Ray.

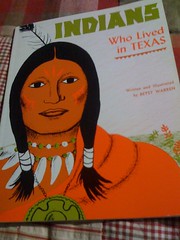

This out-of-print book by Texas author Betsy Warren gives details about the dress, food, and other customs of ten Native American groups that lived in the area we now call Texas. These tribes were the Caddo and the Wichita of Northeast Texas, the Karankawa, the Coahuiltecans, and the Atakapans of the Texas Gulf coast, the Jumanos who farmed in West Texas along the Rio Grande, the Tonkawa of Central Texas, and the hunting tribes of the West Texas plains: Kiowas, Lipan Apaches, and Comanches.

This out-of-print book by Texas author Betsy Warren gives details about the dress, food, and other customs of ten Native American groups that lived in the area we now call Texas. These tribes were the Caddo and the Wichita of Northeast Texas, the Karankawa, the Coahuiltecans, and the Atakapans of the Texas Gulf coast, the Jumanos who farmed in West Texas along the Rio Grande, the Tonkawa of Central Texas, and the hunting tribes of the West Texas plains: Kiowas, Lipan Apaches, and Comanches.