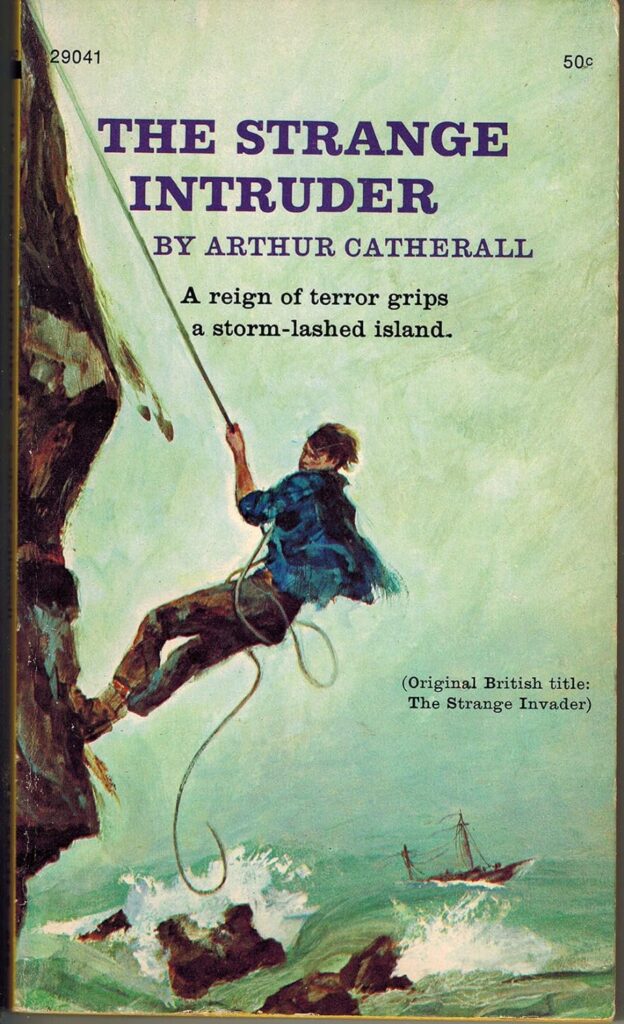

I’ve heard of Arthur Catherall as an author of children’s or young adult fiction, but I’ve always thought of him, without having read any of his books, as a sort of minor, second rate, potboiler fiction writer. Sorry, Mr. Catherall. If The Strange Intruder is a good example of the rest of Catherall’s work, he’s actually a first rate adventure writer. Maybe I had that potboiler idea because Catherall was so prolific: he wrote dozens of books using his own name and dozens more using seven different pseudonyms. Busy man.

Anyway, The Strange Intruder is a coming of age story about a sixteen year old boy, Sven Klakk, who lives on the island of Mykines in the Faroe Islands. You might need a map to locate that island exactly in your mind (I did), but it’s generally northwest of Scotland and the Shetland Islands and west of Norway, southeast of Iceland in the North Sea. In my 50 cent Archway paperback copy of the book there is a handy-dandy map, so there probably will be one in yours, too, whatever copy you end up reading.

Catherall “voyaged to the Faroe Islands, the locale of this story, and spent some time there, getting to know the islanders and their way of life.” This familiarity with the setting shows in the descriptions of not only the flora and fauna of the island, but also the way the people talk, and work, and make decisions, and form their community life. Of course, I was reminded of the TV series Shetland, with the Shetland Islands nearby, but this island Mykines in the 1960’s, is its own place with its own remote and closely bound culture and way of life.

“A reign of terror grips a storm-lashed island.” There is storm and shipwreck and peril and a big surprise that leads to even more danger and peril, and I can’t say much more for fear of spoiling the story. But just know that you won’t encounter any political agendas or preaching or morals to the story—just pure adventure and suspense and character growth and wildness. I recommend this book, and on the strength of this one, you might want to at least check out Catherall’s many other stories, too.