Becoming Ben Franklin: How a Candle-Maker’s Son Helped Light the Flame of Liberty by Russell Freedman.

Becoming Ben Franklin: How a Candle-Maker’s Son Helped Light the Flame of Liberty by Russell Freedman.

I have several books about Benjamin Franklin in my library, including Franklin’s own autobiography. However, the other four Franklin books that I own are all written for younger readers. Becoming Ben Franklin, despite its relatively short seventy-seven pages, is written on a middle school or high school level as a basic introduction to the life of our most celebrated founding father.

Russell Freedman, of course, is quite well-known himself in the field of children’s nonfiction, having won the Newbery Award for his photobiography of Lincoln and Newbery Honors for books about Eleanor Roosevelt and about the Wright brothers. He begins his book on Benjamin Franklin with Franklin’s arrival in Philadelphia at the age of seventeen, a runaway apprentice “with a mind of his own.” In Freedman’s treatment, as in most other biographies of Franklin, Benjamin Franklin comes across as the quintessential self-made man. He asked for financial help from his father when he decided to set up a print shop in Philadelphia, but dad was not prepared to give such help without some proof that Benjamin was serious and likely to succeed. Pennsylvania Governor William Keith promised young Ben introductions and letters of credit and sent him off to England to pick out equipment for his new business, but when Ben arrived the introductions and the loans were nonexistent. So Ben was again on his own.

It seems from the narrative that although Benjamin Franklin was something of an eccentric with his “air baths” and his experiments in electricity, he won his place in the world by dint of hard work, experimentation with good ideas, and perseverance. Ben Franklin is a good subject for a children’s biography because the author can choose whether to emphasize Ben’s quirkiness, hard work, innovative ideas, or influence in politics or science or international affairs.

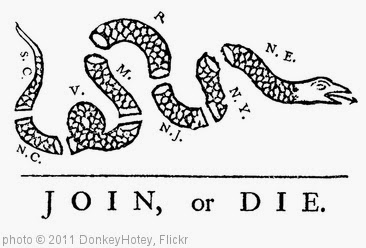

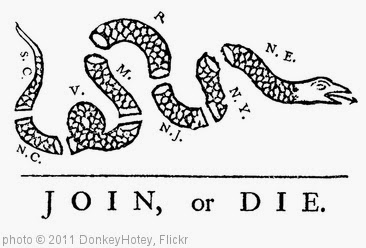

As I said, this biography would be a good, solid middle school introduction to the life of Ben Franklin. Only one caveat: On page 28, there is a picture of this cartoon from the pen of Mr. Franklin. The caption reads in part: “The parts of the segmented snake are labeled for South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and New England (which was actually four colonies). Delaware and Maryland are missing.” Obvious mistake. I’m not sure what is missing (Connecticut? Or was it one of the four NE colonies? Maybe Georgia?), but Maryland is NOT missing. Picky, I know, but children’s informational books should be accurate to the nth degree. I wouldn’t buy it with that error in it. However, you may be willing to overlook it since the book is well-written and informative otherwise.

As I said, this biography would be a good, solid middle school introduction to the life of Ben Franklin. Only one caveat: On page 28, there is a picture of this cartoon from the pen of Mr. Franklin. The caption reads in part: “The parts of the segmented snake are labeled for South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and New England (which was actually four colonies). Delaware and Maryland are missing.” Obvious mistake. I’m not sure what is missing (Connecticut? Or was it one of the four NE colonies? Maybe Georgia?), but Maryland is NOT missing. Picky, I know, but children’s informational books should be accurate to the nth degree. I wouldn’t buy it with that error in it. However, you may be willing to overlook it since the book is well-written and informative otherwise.

Some other Ben Franklin titles for younger children:

Some other Ben Franklin titles for younger children:

Aliki in The Many Lives of Benjamin Franklin writes: “Benjamin Franklin was born with just one life. But as he grew, his curiosity, his sense of humor and his brilliant mind turned him into a man with many lives.” Aliki’s prism for Ben Franklin is the “man of ideas.” It’s good book that would fit right in to today’s popularity of “graphic” nonfiction with its cartoon panel pages, but it’s out of print.

What’s the Big Idea, Ben Franklin? by Jean Fritz takes much the same perspective as Aliki’s book, but with an emphasis on Franklin’s comical and entertaining side and his nonconformist, can-do attitude. “Benjamin would have liked to do nothing but experiment with his ideas, but people had discovered that he was more than an inventor. Whatever needed doing, he seemed able and willing to do it.”

Poor Richard in France by F.N. Monjo is narrated by Franklin’s grandson, Benny, and focuses on Ben Franklin’s time in France during the American Revolution when he was working to get the French to support the Americans in their fight against the British. In this story Franklin is a wise and indulgent old grandfather who always answers Benny’s questions and outfoxes both the British and the French. The emphasis is on Franklin’s wisdom. (This one is my favorite of the lot. The voice of young Benny and his interactions with his grandfather are a delight.) Unfortunately, Monjo’s book is also out of print.

Benjamin Franklin: Young Printer by Augusta Stevenson is one of the Childhood of Famous Americans series of fictionalized biographies of great Americans. Stevenson’s Ben Franklin is more serious and mature for his age. He gives good advice to his age mates, and he’s “the best apprentice in the world.” Stevenson tells stories about young Ben in the same vein as George Washington and the Cherry Tree, stories that emphasize how Ben was, even in his youth, a diligent, honest, and tenacious young man, a character to be admired and emulated.

Becoming Ben Franklin is a good addition to the stable of children’s biographies about the great man. It’s pitched for an older audience, but still quite accessible with an easy to read layout and design and lots of period illustrations, and at least one factual error that should have been noticed by a proofreader before it got into print.

Quentin, Sarah, Ben and Cat are kids with one thing in common: they each experienced a head injury that brought them to the International Center for Advanced Neurology (I-CAN) to try to recover their brain and themselves. As Cat says, “The most terrifying thing about hitting your head so hard is when you wake up missing a piece of yourself. . . Things you could once do–kick a soccer ball without losing your balance, play air guitar with your best friend, climb in a kayak, or stand steady on the houseboat deck to pinch dead blossoms off the geraniums–all gone. Erased. Whole pieces of you are missing because your brain bumped against your skull.”

Quentin, Sarah, Ben and Cat are kids with one thing in common: they each experienced a head injury that brought them to the International Center for Advanced Neurology (I-CAN) to try to recover their brain and themselves. As Cat says, “The most terrifying thing about hitting your head so hard is when you wake up missing a piece of yourself. . . Things you could once do–kick a soccer ball without losing your balance, play air guitar with your best friend, climb in a kayak, or stand steady on the houseboat deck to pinch dead blossoms off the geraniums–all gone. Erased. Whole pieces of you are missing because your brain bumped against your skull.”