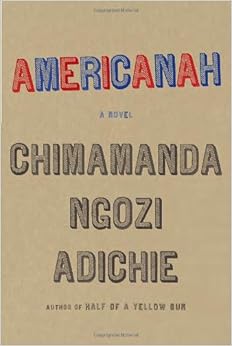

Our family–me, some of my adult children and their spouses–are participating in a book club together this year. We’re taking turns choosing a book a month. The July book was The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel. It was a novel about a Ponzi scheme and the people who become enmeshed in it, both before and after the scheme goes bust. In August we read a book of short stories, The Thing Around Your Neck by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie who also wrote the novels Purple Hibiscus, Half of a Yellow Sun, and Americanah. She is a good writer, and although I always enjoy full length novels more than I do short stories, these stories were well worth the read.

I started a couple of weeks ago and read one story each night before bedtime. It was a good way to digest a book of seemingly unrelated short stories that are at least somewhat tied together by theme if not characters or plot. Reading only one story at a time gave me an opportunity to reflect and learn from each one.

The stories are about cultural encounter and clash between men and women, parents and children, Christian and Muslim, younger and older generations, modern and ancient, Nigeria and the United States. For the most part the tone and the outlook of each story are rather bleak. With one exception, the cultural and generational encounters in each of the stories are fraught with misunderstanding and even tragedy. In the first story “Cell One” a young man learns a lesson when he is imprisoned for a few days. In the second, “Imitation”, a properly submissive young wife confronts her husband’s blatant adultery. Another story is about a black woman from Nigeria who becomes the girlfriend and lover of a white man in Hartford, Connecticut. As in the other stories, the romance/story ends sadly, not with bang but rather a whimper.

The one story that shows two people coming to some sort of bridge of cultures is called “A Private Experience.” Two women are trapped together in a small store by violence and riots in the streets of a small market village in Nigeria. One is a Hausa Muslim woman, a mother; the other is a young Christian college student from the city. They are different is so many ways: economic status, religion, age, experience. And yet as they are thrown together, the two learn to trust and help each other, and they survive. This tale, too, does not have a happy ending, and yet there is a spark of hope in the patient endurance of the Muslim woman and the awakening understanding and empathy of the young Christian student.

And on it goes. A Nigerian nanny misunderstands the actions of her artist employer. A young wife whose son has died is applying for asylum in the United States, but she is unable to explain the complexities of her situation to the customs official who is taking her application. There’s a Cain and Abel story featuring a girl and her older, favored brother. Two Africans in college housing become friends and bond over their grievances about past lovers in spite of their differing religious perspectives. An arranged marriage sours very quickly.

Then, the last and culminating story , “The Headstrong Historian”, tells of a grandmother and the granddaughter who carries on her strength and cultural awareness even though the interceding generation has been Christianized and diminished by white colonization. In all of these stories, when it appears, Christianity is dour and powerless, never a fulfillment of African destiny and understanding, but rather a threat to the deep roots of African greatness or an empty husk to be discarded in the wake of modern twentieth century wisdom. This story begins when the grandmother is young in the late nineteenth century, immersed in African thought patterns and African religion and African community life. The next generation, the son and his wife, accept Christianity, Catholicism, and are made weak and pitiful and rigid by the tenets of the new religion. Then, finally comes the granddaughter, a new, educated, strong woman who learns her true history and goes back to her roots “reimagining the lives and smells of her grandmother’s world.” She writes a book, subtitled A Reclaimed History of Southern Nigeria. But nothing in the story indicates that the granddaughter understands the darker elements of attempted murder and revenge and slavery and mistreatment of women that form part of her history just as much as the depredations of colonialism. The granddaughter changes her name from Grace to Afamefuna, “My Name Will Not Be Lost”, but I wonder if she really knows the meaning and background of her new-old name.