Archie comics had been around for years, since 1941, but in 1969 The Archies, a Saturday morning cartoon band that actually consisted of a group of studio musicians managed by Don Kirshner, has their one and only #1 hit song. The Archies’ “Sugar, Sugar” was the 1969 number-one single of the year in the U.S., UK, and South Africa.

Archives

1969: Events and Inventions

February 4, 1969. In Cairo, Yasser Arafat is elected Palestine Liberation Organization leader at the Palestinian National Congress.

March 7, 1969. 70 year old Golda Meir, head of the Israeli Labor Party, becomes Israel’s new prime minister.

April 4, 1969. In Houston, Dr. Denton Cooley implants the first temporary artificial heart in a man, Hanskell Karp, who lives for 65 hours.

April 9, 1969. The supersonic airliner Concorde 002 takes to the air in the UK for a maiden flight of 21 minutes.

July 21, 1969. Neil Armstrong becomes the first man to walk on the moon.

August 15, 1969. The British government sends troops into Derry, Northern Ireland to restore the peace between groups of Protestant and Catholic street fighters in the war-torn city. Troops will also be sent to Belfast to break up fighting there.

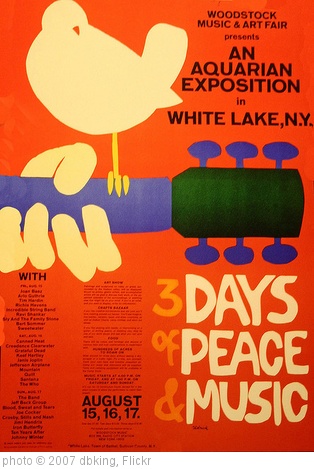

August 15-17, 1969. The world’s biggest rock festival is held at Woodstock in upstate New York. Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Joan Baez, The Who, and Santana are a few of he many performers at the festival.

August 15-17, 1969. The world’s biggest rock festival is held at Woodstock in upstate New York. Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Joan Baez, The Who, and Santana are a few of he many performers at the festival.

September, 1969. North Vietnamese president Ho Chi Minh dies as the war in Vietnam continues.

September, 1969. In Libya, a group of army officers, led by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, seize powere while King Idris of Libya is out of the country. Gaddafi will rule Libya until his death in 2011.

September 28, 1969. The Social Democrats and the Free Democrats receive a majority of votes in the German parliamentary elections, and decide to form a common government. Willy Brandt becomes chancellor, the first Social Democrat to be elected in 39 years.

October, 1969. Civil war rages in Nigeria as the rebel republic of Biafra fights for independence from Nigerian rule. 300,000 civilian refugees in Biafra are facing starvation as the Nigerian government has stopped Red Cross flights carrying relief aid. Nigeria says that the Biafran rebels are using the flights to get arms as well as food.

The Devil in Pew Number Seven by Rebecca Nichols Alonzo

I am in a quandary. I don’t want to discourage anyone form reading this memoir, a true story that carries a wonderful message about the necessity of forgiveness, even in the direst of circumstances.

However, to be honest, the book could have been edited down to about half or three-fourths of its almost 300 pages and not have lost a thing. If you’re a good skimmer, you’ll really appreciate this story of a pastor and his family terrorized and very nearly destroyed by a man who acts like the devil incarnate. In 1969, Robert Nichols moved with his family to Sellerstown, North Carolina to serve as pastor of the Free Welcome Holiness Church. As the name of the church indicated, the Nichols family was welcomed by the community, except for one man, Mr. Horry James Watts, who lived across the street from the parsonage and occupied pew number seven in the Free Welcome Church every Sunday morning. The violence and harrassment began with threatening phone calls and escalated until . . . No spoilers here.

However, to be honest, the book could have been edited down to about half or three-fourths of its almost 300 pages and not have lost a thing. If you’re a good skimmer, you’ll really appreciate this story of a pastor and his family terrorized and very nearly destroyed by a man who acts like the devil incarnate. In 1969, Robert Nichols moved with his family to Sellerstown, North Carolina to serve as pastor of the Free Welcome Holiness Church. As the name of the church indicated, the Nichols family was welcomed by the community, except for one man, Mr. Horry James Watts, who lived across the street from the parsonage and occupied pew number seven in the Free Welcome Church every Sunday morning. The violence and harrassment began with threatening phone calls and escalated until . . . No spoilers here.

The amazing thing about the story is the ending. Could you forgive a man who threatened to make you family leave the community where you lived “crawling or walking, dead or alive?” The sction near the end of the book on forgiveness is worth the price of the book because the author speaks from hard-earned experience.

“If I allow myself to go down the pathway of rage and retaliation, several things happen, and none of them are good. Here are my top four:

My sins will not be forgiven by God if I refuse to forgive those who have sinned against me.

I miss an opportunity to show God’s love to an unforgiving world.

I’m the one who remains in jail when I withhold God’s grace by failing to forgive.

If I have trouble forgiving, it might be because I’m actually angry at God, not at the person who wronged me.”

So, I’m recommending this book with the caveat that you’re not to expect deathless prose, just a riveting and inspiring story of nitty-gritty forgiveness and even joy in very difficult circumstances.

Poetry Friday: Roberta Anderson

Roberta Joan Anderson was born on November 7, 1943, in Fort Macleod, Alberta, Canada.

As a teen she listened to rock-n-roll radio broadcasts out of Texas. She bought herself a baritone ukelele for $36 because she couldn’t afford a guitar.

“In a hundred years, when they ask who was the greatest songwriter of the era, it’s got to be her or Dylan. I think it’s her. And she’s a better musician than Bob.”~David Crosby

“She took the clay and moulded it in a way we hadn’t seen before. If you really sort of analyse songwriting at that time, male or female, what she was doing with her structures and her use of melody and her poetry and the voice too, you know that’s just one of the gifts that we’ve had.” ~Tori Amos

Sometimes change comes at you

like a broadside accident

There is chaos to the order

Random things you can’t prevent

There could be trouble around the corner

There could be beauty down the street

Synchronized like magic

Good friends you and me.

Moons and Junes and Ferris wheels

The dizzy dancing way you feel

As ev’ry fairy tale comes real

I’ve looked at love that way

But now it’s just another show

You leave ’em laughing when you go

And if you care, don’t let them know

Don’t give yourself away

I’ve looked at love from both sides now

From give and take, and still somehow

It’s love’s illusions I recall

I really don’t know love at all

Tears and fears and feeling proud

To say “I love you” right out loud

Dreams and schemes and circus crowds

I’ve looked at life that way

But now old friends are acting strange

They shake their heads, they say I’ve changed

Well something’s lost, but something’s gained

In living every day

I’ve looked at life from both sides now

From win and lose and still somehow

It’s life’s illusions I recall

I really don’t know life at all.

As a child I spoke as a child–

I thought and I understood as a child–

But when I became a woman–

I put away childish things

And began to see through a glass darkly.

Where, as a child, I saw it face to face

Now, I only know it in part

Fractions in me

Of faith and hope and love

And of these great three

Love’s the greatest beauty…

You may know her as singer/songwriter Joni Mitchell.

them by Joyce Carol Oates

7/26/08: I’m over halfway through this book, “the third and most ambitious of a trilogy of novels exploring the inner lives of representative young Americans from the perspective of a ‘class war’.” “The them of the novel are poor whites, separated by race (and racist) distinctions from their near neighbors, poor blacks and Hispanics.” The words of explanation are Ms. Oates’ commentary on her own novel in an afterword at the end of the book.

7/26/08: I’m over halfway through this book, “the third and most ambitious of a trilogy of novels exploring the inner lives of representative young Americans from the perspective of a ‘class war’.” “The them of the novel are poor whites, separated by race (and racist) distinctions from their near neighbors, poor blacks and Hispanics.” The words of explanation are Ms. Oates’ commentary on her own novel in an afterword at the end of the book.

I’m finding the novel condescending and full of stereotypes: the spoiled rich girl, the poor but violent young man full of unresolved rage, the eternal victim of that “victimless crime”, prostitution. I’ve been borderline poor, not in the inner city, and I’ve lived among poor people in the city. I don’t believe there is any “class war” in the U.S. Racism, yes. A division of classes, yes. But the poor people I have known mostly don’t think of themselves as poor, resent being classified as poor, intend to become middle class or rich as soon as hard work or a lucky break will enable that to happen. And there are all sorts of poor people. Some are hard working and others are lazy. Some are conscientiously religious, and others are profane and vulgar. Some are happy; others are morbidly depressed. Ms. Oates’ them are all the same: materialistic, violent, and devoid of moral values (probably because moral values are “middle class values” in the jargon and the perspective of the sociologist).

Ms. Oates again: “Few readers of them since its 1969 publication have been them because them as a class doesn’t read, certainly not lengthy novels.” How patronizingly untrue. And yet, Ms. Oates’s main character, Maureen, one of them, reads and enjoys Jane Austen and other novels. Perhaps the author is correct in writing that the poor as a class don’t read novels like them because they generally prefer hope and optimism to a vision that condemns them to generations of poverty and violence and victimhood.

7/27/08: I was sitting in church this morning thinking about Loretta, Maureen, and Jules, the central characters in them. Even though I still believe they tend toward stereotype, there are people out there, them, who fit the stereotype. What does the Gospel have to say to the Lorettas, hard as nails, seen it all, loud, brash and poverty enslaved? How can the Church, Jesus’s church, reach and speak to the Maureens of the city, victims of a bad home, bad education, a dearth of values, and their own longing for something better? If Jesus himself could speak to the Samaritan woman who was both of these women in one, can’t the Church somehow act redemptively in the lives of women like these as Christ’s representatives? And Jules. At a point in the story Jules, the smart but criminally destined young man, has a Bible and time and inclination to read it. (He’s in the hospital.) But he says, “My main discovery is that people have always been the same, lonely and worried and hoping for things, and that they have written their thoughts down and when we read them we are the same age as they are.” Jules finds hope and fellow feeling in the Scriptures but no salvation, no change. How could Christians, how could God’s Spirit, reach a man so embedded in sin and degradation and lift him up, not into the middle class, but into heaven itself? I’m not sure. I know it happens for some people, but not for others. I do know that the Gospel of Jesus Christ is the only hope for people like Loretta, Maureen, and Jules . . . and for people like me, good old middle class me, just as sinful and degraded in my own middle class way.

There you have it. I have already this week established myself as a philistine and an anachronism. A family member, who shall remain nameless, accused me of calling her an elitist when I confessed my lack of appreciation for one of her favorite novels, Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer. And now I fear that the kindred spirit-ness that a certain blogger and I have shared in the past is tinged with a lack of understanding on my part. I will say that them made me think about poverty and racism and class struggle and sin, but I didn’t enjoy reading it and don’t wish to repeat the experience anytime soon. (Maybe some of the other novels of Joyce Carol Oates would suit me better? She’s quite a prolific writer, and this one is the only one I’ve read.)

So be it. Give me Dickens or Dostoyevsky or Victor Hugo or just a rousing adventure by Tolkien or Dumas. There’s plenty of poverty and and evil and violence in those authors’ books, but there’s also something else, a lack of inevitabliity, dare I say, a sense of hope? From the twentieth century, I’ll take Alan Paton or P.D. James, Dorothy Sayers or even my newest discovery Wendell Berry (something of an anachronism himself). But saints preserve me from the modern sociological novel.

Joyce Carol Oates fans, we’re still friends, right?