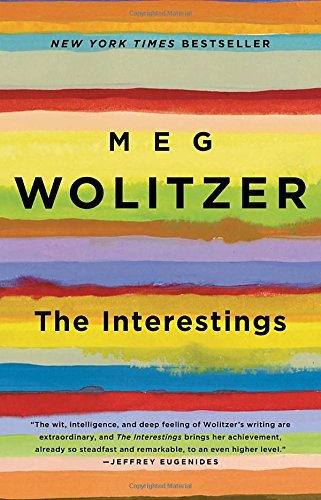

I tried to become absorbed in this rather self-centered and pretentious novel because the cast of characters who inhabit the novel are my age mates. The six friends who make up the group who call themselves “the Interestings” are teenagers in the mid-seventies, college students in the late seventies and early eighties, get married (or at least co-habit) in the eighties, really marry and have children in the nineties, and find themselves midddle-aged and evaluating the consequences of their life decisions in the twenty first century. That’s me, except for the co-habitation part, and except for the fact that these are artsy people. Or artsy wannabes. And rich, mostly. And New Yorkers, insufferably proud and parochial New Yorkers. If it weren’t for all those differences, I could have been any one of the characters in this novel.

I tried to become absorbed in this rather self-centered and pretentious novel because the cast of characters who inhabit the novel are my age mates. The six friends who make up the group who call themselves “the Interestings” are teenagers in the mid-seventies, college students in the late seventies and early eighties, get married (or at least co-habit) in the eighties, really marry and have children in the nineties, and find themselves midddle-aged and evaluating the consequences of their life decisions in the twenty first century. That’s me, except for the co-habitation part, and except for the fact that these are artsy people. Or artsy wannabes. And rich, mostly. And New Yorkers, insufferably proud and parochial New Yorkers. If it weren’t for all those differences, I could have been any one of the characters in this novel.

So, other than age, I don’t really have much in common with Jules and Ethan and Ash and Goodman and Jonah and Cathy. Honestly, I’m glad not to have much affinity with these characters because they are not very likable people, except for Ethan who is a teddy bear. Jules, the main viewpoint character, is the outsider who meets the other teens at Spirit-in-the-Woods summer camp for “talented” teens and becomes a part of their oh-so-interesting in-group. But Jules always feels a little outside and a little envious because she’s from suburbia and middle class and not really all that interesting. Ash and Goodman, brother and sister, are rich, not terribly talented or interesting on their own, but backed by lots of money and influence, they can appear to be both. Cathy is a dancer with the wrong kind of body for professional success in dancing. Jonah is a musician, but emotionally damaged, the son of a sixties folk music star. And Ethan is an artist and animator, the real talent in the the group.

In 468 pages, Ms. Wolitzer tells the story of these six people, their friendships, their professional lives, their coupling and uncoupling, their families, and their sexual misadventures. The book could have been about 200 pages shorter and lot better had Ms. Wolitzer left out the long and tedious descriptions of the various characters’ sexual encounters, both within and outside marriage. I get it. Sex is really important to these people. Jules rejects Ethan because she’s not sexually attracted to him, even though he is her best friend. She buys sex toys on a shopping trip with her best girlfriend, Ash. She fantasizes sex with Goodman. She has lots of sex with her live-in boyfriend, then husband, Dennis.

Jonah Bay is gay, so we must have lots of descriptions of homosex, including answers to the questions we all have about how to have sex when one partner is HIV-positive. Then, there’s attempted rape, sex with a clinically depressed person (not much there), sex in marriage, sex in the college dorm, sex while high, unfulfilled sexual attraction, sex with vibrator, no sex, maybe sex, wild sex. Every few pages the author throws in a sex scene, some of which attempt to be titillating but only succeed at being boring. I skimmed a lot.

And, although I read the whole thing, skimming aside, I would say that’s an apt description for the entire book: it tries but fails to be interesting. The characters try but fail to grow to be interesting. Jules tries to be wry and sardonic but only manages to be jealous and lazy, trapped in some ideal past when she “came alive” at camp. Jonah tries to overcome his past as an abused kid, but he never connects with anyone much. Ethan tries to be a good rich and powerful man, but he has to have a major failure, so the author sticks one in, even though it doesn’t seem to be in character. Ash tries to be a feminist and an artist but turns into a a rich housewife like her mom. Goodman doesn’t try ever, and he reaps what he sows. Cathy sort of drops out of the story after providing a convenient plot device. I kept hoping for character development, but all I got was more sex scenes and detailed physical descriptions of how ugly or pretty each character was at any given point in his or her life. These descriptions (and the sex scenes) may have been supposed to stand in for character development.

I don’t know to whom to recommend this book. If you are self-absorbed enough to identify with these characters, then you are self-absorbed and won’t find them to be very interesting. Maybe New Yorkers who are not self centered and pretentious could see by reading The Interestings why the rest of us tend to think that they are. Books like this one don’t help to dispel the stereotype.