To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion, 1914-1918 by Adam Hochschild.

Mr. Hochschild also wrote Bury the Chains, a history of the British campaign against the African slave trade that I read and found fascinating in 2007, about the same time the movie Amazing Grace came out. Of course, I was drawn to that book because of the connection to Mr. Wilberforce’s story and because of the Christian history elements of the story. To End All Wars, which focuses on conscientious objectors and anti-war activists in Britain during World War I, didn’t have the Christian element going for it. Most of the anti-war crowd were socialists, labor unionists, and atheists or agnostics. However, it was an absorbing look at attitudes and political alliances in England during the war, and it applies directly to the beginning of the twentieth century, the history I’m going to be teaching very soon to eight high school students at our homeschool co-op.

Mr. Hochschild also wrote Bury the Chains, a history of the British campaign against the African slave trade that I read and found fascinating in 2007, about the same time the movie Amazing Grace came out. Of course, I was drawn to that book because of the connection to Mr. Wilberforce’s story and because of the Christian history elements of the story. To End All Wars, which focuses on conscientious objectors and anti-war activists in Britain during World War I, didn’t have the Christian element going for it. Most of the anti-war crowd were socialists, labor unionists, and atheists or agnostics. However, it was an absorbing look at attitudes and political alliances in England during the war, and it applies directly to the beginning of the twentieth century, the history I’m going to be teaching very soon to eight high school students at our homeschool co-op.

Here’s sampling of facts and quotes I found whilst reading the book:

“A star of the literary war effort was the novelist John Buchan . . . For Thomas Nelson, an Edinburgh publisher, he put his agile pen to workwriting a series of short books that constituted an instant history of the war as it was unfolding. They downplayed British reverses, emphasized acts of heroism, evoked famous battlefield triumphs of times past, scoffed at pacifists, predicted early victory, and overestimated German losses. The first installment of Nelson’s History of the War appeared in February 1915; within four years, with some assistance, Buchan would produce 24 best-selling volumes, totaling well over a million words—by far he most widely read books about the war written while it was in progress.” p. 149.

I found this account of Buchan’s prolific activities interesting because I have tried to read several books by Mr. Buchan, with mixed results. The Thirty-Nine Steps was somewhat melodramatic, but O.K. (Here’s a good review of The Thirty-Nine Steps by Woman of the House.) Greenmantle had lots of rather obscure historical references and geographical details and early twentieth century slang, and I found it rather tough going. (Eclectic Bibliophile’s thoughts on Greenmantle.) I think I started a third book by Buchan, but couldn’t get through it.

“In the trenches, the Christmas season was anything but merry “A high wind hurtled over the Flemish fields, but it was moist, and swept gusts of rain into the faces of men marching through the mud to the fighting-lines and of other men doing sentry on the fire-steps of the trenches into which watercame trickling down the slimy parapets . . . They slept in soaking clothes, with boots full of water . . . Whole sections of trench collapsed into a chaos of slime and ooze.” ~journalist Phillip Gibbs.

“No war in history had seen so many troops locked in stalemate for so long. The year 1915 had begun with the Germans occupying some 19,500 square miles of French and Belgian territory. At its end, Allied troops had recaptured exactly eight of those square miles, the British alone suffering more than a quarter-million casualties in the process. Still an endless stream of wounded flowed home, and still the newspapers were filled with list of those killed or missing.” p. 173.

All of the descriptions of conditions in the trenches are horrific. I do not understand how men continued to live and fight in such conditions, and then with nothing to show for their time and effort except more injured and dead soldiers.

1917: “In the previous two years, despite the millions of soldiers killed and wounded, nowhere along its entire length of nearly 500 miles had the front line moved in either direction by more than a few hours walk. Military history had not seen the likes of this before, and the Germans were no less frustrated than the Allies.” p. 246.

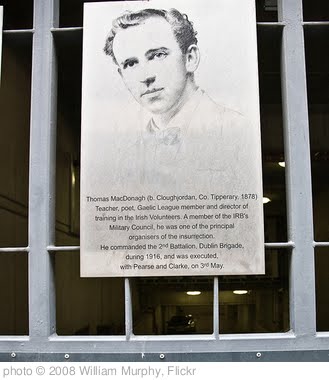

“In early April 1917 the German government provided what later became famous as the ‘sealed train’ to the Bolshevik leadership. It carried them across Germany, from the Swiss border to the Baltic Sea, where they could embark for Petrograd and make their revolution. The 32 Russians in threadbare clothes who took the journey would, within a mere six months, leapfrog from penniless exile to the very pinnacle of political power in a vast realm that stretched from the Baltic to the Pacific. . . . In Churchill’s words, Germany had sent Lenin on his way to Russia ‘like a plague bacillus.'”

And so Lenin and his comrades went back to Russia, and so began the Communist takeover of Russia and the transformation of much of Europe and Asia into a Communist gulag.

From a book (ghost)written by atheist Bertrand Russell in support of freeing conscientious objectors who were imprisoned in Britain:

“They maintain, paradoxical as it may appear, that victory in war is not so important to the nation’s welfare as many other things. It must be confessed that in this contention they are supported by certain sayings of our Lord, such as, ‘What shall it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose his own soul?” Doubtless such statements are to be understood figuratively . . . They believe . . . that hatred can be overcome by love, a view which appears to derive support from a somewhat hasty reading of the Sermon on the Mount.”

Russell was an anti-war activist himself, and he was subtly making fun of Christians who become involved in war fever and go to war in spite of the “blessed are the peacemakers” of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. How would you answer him? Is pacifism the obvious message of the New Testament? I have been a pacifist and am now a reluctant supporter of defensive and “just war”, but I must admit I have qualms. I do believe that hatred will ultimately be overcome by love (“love wins”), but in the meantime the innocent deserve to be protected. The slave should be freed if it is within our power to do so. On the other hand, in retrospect, World War I seems to me to have been neither just nor necessary, but it is hard to know what could have be done to stop it once it had begun. Difficult stuff.