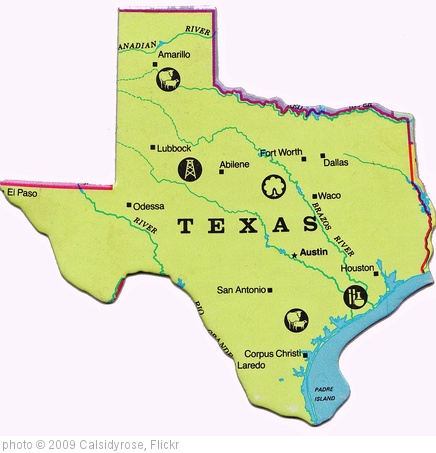

I must admit that I’m a proud Texan with a mild Texas accent and a whiff of Texas braggadocio. And I think reading books by Texan authors or books set deep in the heart of Texas is a great way to spend a summer afternoon.

Adams, Andy. The Log of a Cowboy. Semicolon review here.

Anderson, Jessica Lee. Border Crossing. YA novel about an Hispanic teen who is dealing with paranoid schizophrenia. I will be looking for a copy of this novel soon.

Appelt, Kathi. The Underneath. Animal story from the Big Thicket of East Texas. Semicolon review here.

Baker, Betty. Walk the World’s Rim. The tragic story of a Native American boy named Chacko and of Esteban, the slave who accompanied Coronado on his search for the Seven Lost Cities of Cibola.

Baker, Betty. Walk the World’s Rim. The tragic story of a Native American boy named Chacko and of Esteban, the slave who accompanied Coronado on his search for the Seven Lost Cities of Cibola.

Baker, Nina Brown. Texas Yankee. A children’s biography of inventor Gail Borden.

Beatty, Patricia. Wait for Me, Watch for Me, Eula Bee. Captured-by-Indians fiction set in West Texas, 1860’s. Semicolon review here.

Bertrand, J. Mark. Back on Murder. A murder mystery/police procedural set in Houston. Sequels are Pattern of Wounds and Nothing to Hide. Semicolon review here.

Bissinger, H.G. Friday Night Lights. The book that started it all, led to a movie and then a TV Series. I read that the people of Odessa are still mad at Bissinger for his portrayal of their town. I’m not mad, but I do think he probably misunderstood a few things. Semicolon book review here.

Brammer, Billy Lee. The Gay Place. This novel is supposed to be about LBJ in disguise. I haven’t read it, but I’d like to check it out.

Brett, Jan. Armadillo Rodeo. A picture book about Bo the Armadillo who longs for adventure.

dePaola, Tomie. The Legend of the Bluebonnet. A picture book telling the Native American legend concerning Texas’s state flower, the bluebonnet.

Dobie, J. Frank. Up the Trail from Texas. This book, published in 1955, is one of the Landmark History series from Random House. J. Frank Dobie wrote over twenty books about the history, folklore, and traditions of Texas. If anyone was qualified to write a Landmark history book about the history of the cattle, cowboys, and trail drives of Texas, it was Mr. Dobie.

Donovan, James. The Blood of Heroes: The 13-Day Struggle for the Alamo–and the Sacrifice That Forged a Nation. Semicolon review here. Al Mohler recommends it.

Donovan, James. The Blood of Heroes: The 13-Day Struggle for the Alamo–and the Sacrifice That Forged a Nation. Semicolon review here. Al Mohler recommends it.

Egan, Timothy. The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl. Semicolon review here.

Erdman, Louella Grace. The Edge of Time. Newlyweds in North Texas build a farm and a marriage in the middle of ranching country.

Erickson, John. Moonshiner’s Gold. Great action-packed adventure with engaging characters and a lot of history sneaking in through the back door. John Erickson is known for his Hank the Cowdog series, but this stand-alone adventure is just a good as the Hank books and should be just the right reading level for most sixth graders.

Erickson, John. The Original Adventures of Hank the Cowdog. Early and middle grade readers will enjoy this series of tales about a lovable cowdog.

Ferber, Edna. Giant is really a fantasy. I just don’t know very many people in Texas who live like the Benedicts or who ever did. And Ms. Ferber was from Michigan. But Giant is a fun Texas fantasy, and it does manage to give the sense of how everyone in Texas wants to at least pretend that Texas and all its cultural appendices are bigger than life.

Ferber, Edna. Giant is really a fantasy. I just don’t know very many people in Texas who live like the Benedicts or who ever did. And Ms. Ferber was from Michigan. But Giant is a fun Texas fantasy, and it does manage to give the sense of how everyone in Texas wants to at least pretend that Texas and all its cultural appendices are bigger than life.

Fritz, Jean. Make Way for Sam Houston. Semicolon review here.

Garland, Sherry. In the Shadow of the Alamo. This YA novel set during the Texas Revolution is different because it’s told from the perspective of a Mexican boy, Lorenzo, who’s conscripted into Santa Anna’s army and forced to fight the Tejanos at the Alamo and at San Jacinto.

Garland, Sherry. A Line in the Sand: The Alamo Diary of Lucinda Lawrence Gonzales, Texas, 1836. A Dear America series book set at the battle of the Alamo.

Gibbs, Stuart. Belly Up! Semicolon review here.

Gibbs, Stuart. Belly Up! Semicolon review here.

Gipson, Fred. Old Yeller. Classic. (I once had Mr. Gipson’s ex-wife for an English teacher in high school. I think. At least that was the rumor in my high school.)

Graves, John. Goodbye to a River. A story of the author’s canoe trip down the Brazos River.

Greene, A.C. A Personal Country. Memoir/essays about the culture and people of West Texas, Abilene in particular.

Harrigan, Stephen. The Gates of the Alamo. Adult fiction. Semicolon review here.

Hemphill, Helen. The Adventurous Deeds of Deadwood Jones. An engaging Western novel about cowboy life for middle school readers. Semicolon review here.

Hoff, Carol. Johnny Texas. Sequel is Johnny Texas on the San Antonio Road.

Hoff, Carol. Head to the West. A Christmas excerpt from this story of Galveston immigrants.

Holt, Kimberly Willis. When Zachary Beaver Came to Town. National Book Award winner.

Holt, Kimberly Willis. When Zachary Beaver Came to Town. National Book Award winner.

Janke, Katelan. Survival in the Storm: The Dust Bowl Diary of Grace Edwards, Dalhart, Texas 1935. Another Dear America journal-style book for middle grade and young adult girls.

Jiles, Paulette. News of the World. Excellent adult novel takes place in post-Civil War Texas, about 1870.

Karr, Kathleen. Oh Those Harper Girls! Semicolon review here.

Kelly, Jacqueline. The Evolution of Calpurnia Tate. Middle grade fiction set in 1899. Semicolon review here.

Kelton, Elmer. The Day the Cowboys Quit. Kelton was born in Crane, Texas, and he used to live in San Angelo, my hometown.

Kelton, Elmer. The Time It Never Rained. Top ten Texas novels that I have read. This one should be on every Texan’s reading list.

Kelton, Elmer. Lone Star Rising: The Texas Rangers Trilogy. The Buckskin Line, Badger Boy and The Way of the Coyote. Semicolon review here.

Kelton, Elmer. Lone Star Rising: The Texas Rangers Trilogy. The Buckskin Line, Badger Boy and The Way of the Coyote. Semicolon review here.

Lake, Julie. Galveston’s Summer of the Storm. Semicolon review of this children’s fiction book set before and during the Galveston hurricane of 1900. It starts with a very lazy Texas summer with Texas foods and hot weather and front porches and grandmother’s house. Then disaster!

Larson, Eric. Isaac’s Storm. Semicolon review of this nonfiction tome about the man who was the chief weatherman for the U.S. Weather Bureau on Galveston Island in 1900.

Matthews, Sally Reynolds. Interwoven. A memoir by a pioneer woman about life on the Texas frontier.

Meacham, Leila. Roses. Tumbleweeds: A Novel. I haven’t read these “family saga” novels by a Texas author and set in East Texas and Amarillo, respectively, but they sound intriguing.

Meyer, Carolyn. Where the Broken Heart Still Beats. YA historical fiction about Indian captive Cynthia Ann Parker.

Meyer, Carolyn. Where the Broken Heart Still Beats. YA historical fiction about Indian captive Cynthia Ann Parker.

Meyer, Carolyn. White Lilacs. Early 1920’s, segregation and racial conflict. Here it is reviewed at Becky’s Book Reviews.

Michener, James A. Texas. Typical Michener, somewhat mythologized, but sprawling and readable.

Moss, Jenny. Winnie’s War. Semicolon thoughts here.

Murphy, Jim. Inside the Alamo. This nonfiction account of the famous Battle of the Alamo is a good introduction for grown-ups, too.

Owens, Virginia Stem. At Point Blank: A Suspense Novel. A very satisfying little murder mystery set in rural Texas just outside Houston. Sequels are Congregation and A Multitude of Sins.

Reading, Amy. The Mark Inside: A Perfect Swindle, A Cunning Revenge, And A Small History Of The Big Con. I haven’t read this nonfiction book either, but I saw it recommended at NPR’s website.

Rinaldi, Ann. Come Juneteenth. Slavery in Texas during and after the Civil War.

Sachar, Louis. Holes. Set in a sort of mythical, contemporary Texas, this Newbery-award winning novel is just right for a sweltering hot Texas afternoon.

Shefelman Janice. Comanche Song. Semicolon review here.

Shefelman Janice. Comanche Song. Semicolon review here.

Shefelman, Janice. Spirit of Iron. Semicolon review here.

Smith, Sherri. Flygirl. YA WWII fiction about an African-American girl who “passes” for white and becomes a WASP (Women’s Air Force Service Pilot). Semicolon review here.

Stokes, David R. Apparent Danger: The Pastor of America’s First Megachurch and the Texas Murder Trial of the Decade in the 1920’s (aka

The Shooting Salvationist: J. Frank Norris and the Murder Trial that Captivated America) Semicolon review here.

Thomason, John W. Lone Star Preacher. “Traces the life and times of a fiery Methodist preacher in East Texas during the Civil War era.” This novel joins my lengthy TBR list.

Tinkle, Lon. 13 Days to Glory: The Siege of the Alamo. You can never read too many books about the Alamo, and this one is classic.

Valby, Karen. Welcome to Utopia: Notes from a Small Town. “The book is a portrait of a small town in transition, a town that is growing globally and perhaps even philosophically, if not physically.” ~Booklist

Wisler, G. Clifton. All for Texas: A Story of Texas Liberation. 13-year old Thomas Jefferson Byrd gets caught up in the War for Texas Independence.

Wisler, G. Clifton. Buffalo Moon. Semicolon review here.

Wisler, G. Clifton. Winter of the Wolf. Semicolon review here.

Wisler, G. Clifton. The Wolf’s Tooth. Semicolon review here.

Wood, Jane Roberts. The Train to Estelline. From this list at Texas Reads.